It’s kind of pointless (and usually incorrect) to say that listening to records was “better” in the past. So, I’ll just say that listening to records was different in the past.

I never had a lot of money for records, even into my 20s, so when I bought something new, I really listened to it. Over and over. Sometimes, the same album for weeks at a time (I feel like The Heartbreakers’ L.A.M.F. stayed on my turntable for a couple months). I studied and absorbed them as groups of songs.

What’s funny is I remember the vibe of the room where I first heard a particular record. I can hardly remember what I did yesterday, but I remember all the rooms and all the vibes. Music can imprint memories on us that way. If the record became important to me, the memory of that first listen could grow mythic. But I don’t think I can overstate the impact Bob Marley’s Natty Dread album had on me.

![]()

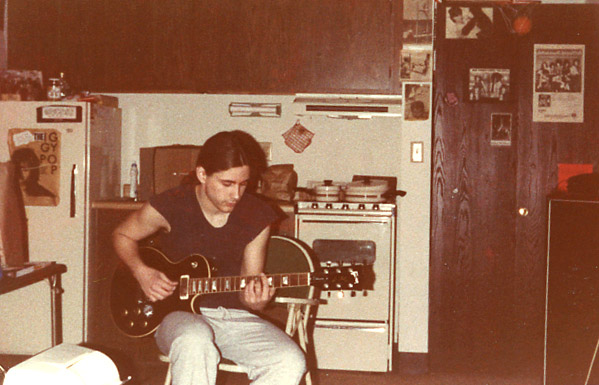

I moved into an apartment when I was 17. I had a roommate, but he disappeared not long after we moved in, so for six or seven years, I (mostly) lived there alone. The apartment building was an old converted hotel. A brick and stone monolith taking up an entire city block in downtown St. Paul, Minnesota. On the ground floor were a smattering of closed businesses, a bar, and a Musicland record store.

Downtown St. Paul was in decline in the late 1970s. At five o’clock, the office workers left, and only the underbelly and the poor residents remained. I’m telling you all this because the city contributed to the vibe in my apartment. Like most teenagers who venture out on their own, my few pieces of furniture were third-hand cast-offs and boards balanced on pilfered milk crates. In this picture, I’m sitting on my folding chair in front of my folding table. My indoors were as wobbly, crumbly, and bleak as the downtown streets.

I didn’t have much in the way of lighting, so when I listened to a record at night, I was usually sitting in front of the stereo in the dark, with only a small plastic desk lamp next to the turntable. Just a kid in a small circle of light trying to get a grip on the world. That was the scene when I first listened to Natty Dread.

![]()

I didn’t usually shop at the Musicland store. It was a little mainstream for my taste (the only two records I remember buying there are Prince’s Dirty Mind and Natty Dread). But one night, I walked down to the corner to see if they had any reggae records. A friend had given me a cassette with a pair of Peter Tosh albums on it a few days earlier, and I fell in love with the music. It was an instant connection, reggae and me. I’ve stopped trying to figure out why or justify it somehow. It just was.

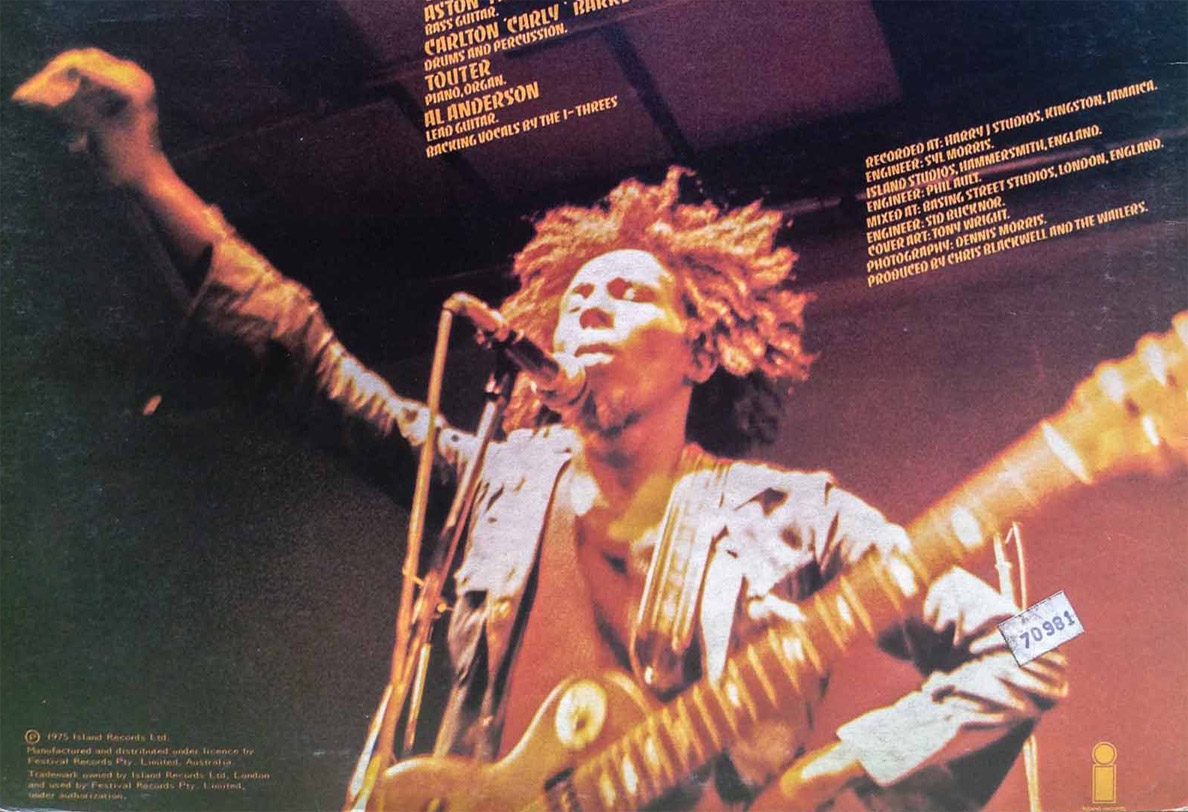

As you might imagine, a chain record store in St. Paul didn’t have many reggae records, but they had a few Tosh and Marley albums. I plucked Natty Dread from the bin, laid down $6.49 or something close to it, and took it upstairs. I chose Natty Dread solely for the picture of Bob on the back cover: ragamuffin style, eyes closed, fist in the air.

It looked like revolution.

And it sounded like revolution.

Natty Dread was not supposed to be the title of the record. Bob released the title song as a single before the album came out under the title Knotty Dread. As in knotty hair; dreadlocks. “Natty” meant well dressed or fancy, so Natty Dread was the opposite of Knotty Dread. Bob was angry when he saw the “natty” title on the LP cover, but he didn’t ask Island to change it.

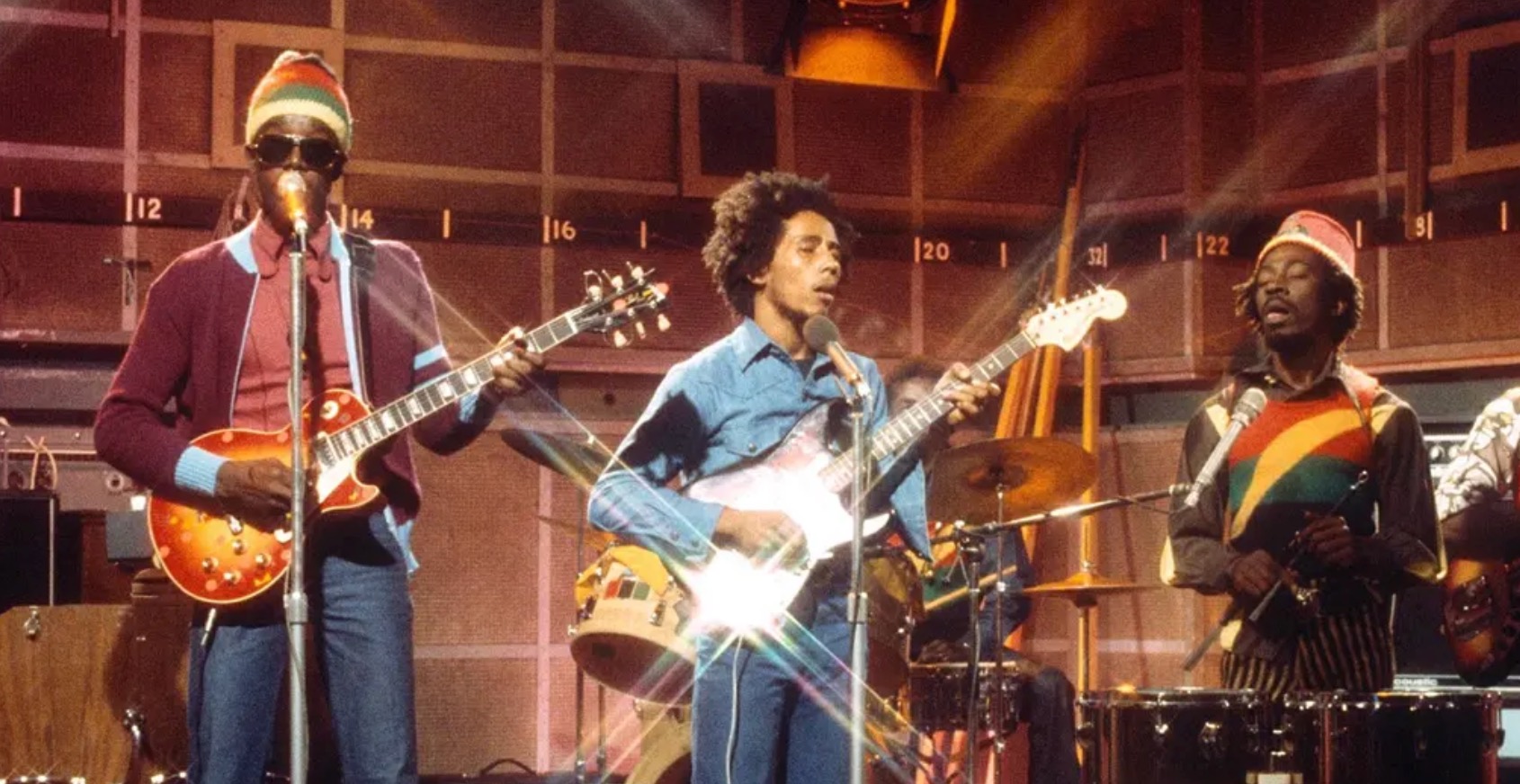

It was Bob’s first album without the original Wailers. The year before Natty Dread, The Wailers released Catch a Fire and Burnin’, their first two “international” albums recorded for Island Records. But Peter Tosh was feeling restricted and unappreciated, and Bunny Wailer didn’t like to tour, so Bob carried on without them.

Natty Dread is the sound of a newly solo Bob. The players on the record are bassist Aston “Familyman” Barrett and his brother, drummer Carlton “Carly,” (American) guitarist Al Anderson, and keyboardist Bernard “Touter” Harvey. Bob plays his distinctive downstroke/upstroke chick-a chick-a rhythm guitar. There’s an uncredited horn section, but I believe it’s David Madden (trumpet) and Vin Gordon (trombone). There are also hand drums, percussion, and harmonica, probably played by Lee Jaffe, an American Bob met a couple of years earlier.

It’s the first Wailers album to feature the female backup singers The I-Threes: Judy Mowatt, Marcia Griffiths, and Rita Marley. They provided the vocal harmonies that were missing in Peter and Bunny’s absence. The women were each successful solo artists in their own right when the began singing with Bob.

![]()

So I sat there on the floor of my apartment, under the plastic lamp, and peeled open the LP. The inner sleeve was a picture sleeve with the lyrics printed on it. That would prove to be more valuable than I could have imagined.

I dropped the needle into the groove.

You’re gonna lively up yourself

And don’t be no drag

Lively up yourself

‘Cause reggae is another bag

Another bag, indeed.

It’s a nice opener, a sneaky prelude considering what was to come. A trick, almost, to lull you into a receptive state. If you only heard Lively Up Yourself, you could get the impression you were about to listen to a good-time party record.

The Natty Dread recording has a somewhat dry and close sound, which just means there isn’t much reverb or echo in the mix. That makes the sound immediate and intimate. If you listen on headphones, it feels like you’re among the musicians. The sound alone was different than anything I’d heard. It was certainly different than the Tosh albums I’d heard. Later, I’d hear plenty of other Jamaican records with the same immediate, small room sound, but this was my first exposure.

The instrumentation on the album sounds sparse, which plays perfectly with the immediate sound. There are eleven musicians and singers, yet most of the songs have a sparse sound. It’s one of the wonderful mysteries of reggae music. A trio can sound like eleven musicians, and eleven musicians can sound like a trio.

The interplay among reggae musicians is very specific and tight despite the often loose feel of the music. When you first encounter it, it’s like an elaborate rhythmic puzzle. I think the precise interplay contributes to the illusion of sparseness.

No Woman, No Cry came next, a song that made it clear that this was not a party record. It was my introduction to Bob Marley, the storyteller.

I remember when we used to sit

In the government yard in Trenchtown

And then Georgie would make the fire light

Log wood burning through the night

Then we would cook cornmeal porridge

Of which I’ll share with you

My feet is my only carriage

So I’ve got to push on through

Bob’s vivid imagery was mesmerizing, and the song’s refrain, “Everything’s gonna be all right,” was joyful. I felt the impact of the music so deeply that it took me by surprise. I had an emotional reaction, and in those days, I stayed far away from any hint of emotion.

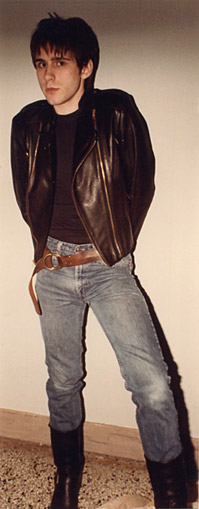

![]()

When I listened to Natty Dread for the first time that night, I was a punk. I worshipped at the altar of the Stooges, New York Dolls, Ramones, and The Clash. I’d played in punk bands since I was 16 years old, and I was a fundamentally angry and cynical young person. In reality, I was a frightened and profoundly sad child, but those feelings manifested as anger and a kind of all-encompassing unpleasantness.

When I listened to Natty Dread for the first time that night, I was a punk. I worshipped at the altar of the Stooges, New York Dolls, Ramones, and The Clash. I’d played in punk bands since I was 16 years old, and I was a fundamentally angry and cynical young person. In reality, I was a frightened and profoundly sad child, but those feelings manifested as anger and a kind of all-encompassing unpleasantness.

So, I was kind of the opposite life force that you might think about when you think of reggae. I grew up with the hippies and peace and love, but our goal as punks was to overthrow all that. To stick a finger in the eye of complacency. It seemed like a good idea at the time.

I don’t want to do a song-by-song rundown here because no one needs that, and it’s not how I remember the first listen. Instead, I have impressions and discoveries.

Them belly full, but we hungry

A hungry mob is an angry mob

Rain a-fall, but the dirt it tough

Pot a-cook, but the food nah ‘nuff

A hungry mob is an angry mob. That kind of truth-telling appealed to the radical punk in me, the “smash the state” kid. But the next lines got to me. Even the rain can’t help; they can’t grow food in the hard dirt of Trenchtown. And when they can cook, it’s not enough food. It’s a sad, sobering image. A bleak but eloquent bit of wordplay.

But then, in the next breath:

Forget your troubles and dance

Forget your sorrows and dance

Forget your sickness and dance

Forget your weakness and dance

Hope.

So much of Bob’s music presents us with the same dichotomy. What it instilled in me over time was the knowledge that we can overcome adversity, but sometimes strength and endurance aren’t enough. Sometimes, we need release and joy. We need to forget our sorrows and dance.

The song So Jah Seh introduces the first really low-frequency sounds that I’d come to associate with reggae. The kick drum, what’s probably a Nyahbinghi “Thunder” drum, and some of the low bass notes rumble. I felt them in my spine. I had never heard low sounds like that in music. I didn’t even know my speakers could do that.

It also introduces the biblical language that permeated roots reggae in the 1970s. Rastafarian concepts were alien to me, of course, as I was an avowed atheist. But here’s Jah—God—saying, “My children might be down, but they have dignity.”

So Jah seh

Not one of my seeds

Shall sit in the sidewalk

And beg bread

Jah also wants us to unite.

And verily, verily, I’m saying unto the-I

[Unite] oneself and love [humanity]

‘Cause puss and dog they get together

What’s wrong with loving one another?

Puss and dog, they get together

What’s wrong with you, my brother?

But then the reality hammer strikes.

And down here

in the ghetto

And down here

we suffer

And finally, resistance.

But I and I, I hang on in there

I and I, I nah [let go]

So Jah Seh is the song on the record that stayed with me and haunted me. The biblical language was somehow…inspirational to me. It was empowering and reassuring. It was regal.

So Jah seh

I’m going to prepare a place

And where I am, thou shall abide

Fear not, oh mighty dread

‘Cause I’ll be there at your side

I wasn’t thinking, “This language makes me feel good. I’ll go be a Rasta now.” That was the furthest thing from my mind. It was just feelings. I was opening up to something unfamiliar. I was still an atheist, but what I would come to learn about Rastafari in the coming months made me believe that maybe I’d come across a spiritual way of life that turned its back on the rotten trappings of religion.

Do humans crave religious community? I don’t think so. If you were raised in a world without religion, you’d never crave it because it wouldn’t exist. And you wouldn’t invent it unless you had a control or exploitation motive. But I do believe we crave a kind of spiritual community with people that has nothing to do with religion and everything to do with love, support, and acceptance.

The album ends with a statement of resistance: Revolution. It begins ominously, with the horn section playing a haunting minor scale melody and the I-Threes intoning, “Revelation reveals the truth.” It’s apocalyptic-sounding music, and the message of the song follows in line.

It takes a revolution

To make a solution

So if a fire, make it burn

And if a blood, make it run

If there must be fire before freedom, let the fire burn. If blood must be spilled, let it run. I’d never heard anything like that from a punk band. Then there’s a line from the song, Talkin’ Blues:

‘Cause I feel like bombing a church

Now that you know that the preacher is lying

I remember thinking, “Did he just say he feels like bombing a church?!”

It was ideas like those that made me evangelize for reggae among my friends. “This music is a hundred times harder than punk rock!” I’d blather incessantly, and it was. It is. The music draws you in, and the stories and ideas hit you hard.

But…

One good thing about music

When it hits, you feel no pain

![]()

I loved the music, so I wanted to know everything about it. I wanted to know what the lyrics meant. I wanted to know who these unique and amazing people were and how they made that sound. There was nowhere to go in the Twin Cities to hang out with Rastas because there were no Rastas in the Twin Cities to hang out with. To learn, I had to read and suss and figure and speculate.

I connected with the lyrics in a lot of ways, but there was still the almost insurmountable barrier of trying to understand Jamaican patois. Natty Dread and other Jamaican records served as my Rosetta Stone(s). There was a lot to be gleaned from the context of the lyrics and storytelling. Slowly, as I read more (mostly in the British weeklies, there wasn’t much to read in American magazines) and listened to more reggae, I became clued in to the philosophy and message.

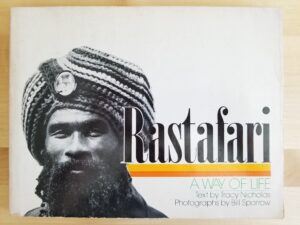

One night, a hippie girl brought me to a hippie bookstore, and I came across the book Rastafari, A Way of Life. I still have the book, but I’m writing this without looking at it again. This is a story of impressions, after all. I remember the book being almost academic, but it provided me with a wealth of information, and it reinforced my growing idea that Rastafari might be a righteous thing to pursue.

One night, a hippie girl brought me to a hippie bookstore, and I came across the book Rastafari, A Way of Life. I still have the book, but I’m writing this without looking at it again. This is a story of impressions, after all. I remember the book being almost academic, but it provided me with a wealth of information, and it reinforced my growing idea that Rastafari might be a righteous thing to pursue.

But the problem with reading about a culture and immersing yourself in the music of the culture is you can end up with a skewed, one-dimensional perception. In my mind, Rastas were righteous people stepping through an unrighteous world. And in a broad, overview kind of way, they are. That’s what drew me in. I wanted to be that righteous person trodding through Babylon. It felt like a new, better kind of punk.

Long story short (Too late for that. -ed), I made my way to Venice Beach, California, and set about finding a Rasta community. The first couple of dreads I befriended on the boardwalk cured my skewed perception by demonstrating that a Rasta or dread is just a human and humans are wildly imperfect. They also made it clear that every dread who claims Rasta doesn’t necessarily live Rasta.

Eventually, I found the Rasta community I was searching for in Topanga Canyon, and it was beautiful. It centered around a band that I wound up playing in, and it’s where I met some of the most wonderful people it’s been my pleasure to know. I grew long dreadlocks and walked the walk. I thought. But there was trouble in paradise.

![]()

The trouble was Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie, who Rastas consider to be God on earth. The second coming. I studied everything I was supposed to study, and I understood why Rastas see Selassie as God, but there was something in me that couldn’t come to grips with Selassie as God.

If you’ve ever spent time with a group of Rastas, you may have heard a familiar call and response. Someone will shout, “Jah!” and everyone within earshot answers, “Rastafari!” I never felt right saying “Rastafari,” even though I considered myself a Rasta by that point.

One of the keyboard players in the band had a habit of testing me. I think he may have been a little suspect of the white person in their midst claiming Rastafari. It was just little things, but he constantly challenged me. It was good he did it, actually, because it forced me to challenge myself and my beliefs.

One day, he asked me, “How come when I say ‘Jah,’ you never say, ‘Rastafari’?”

I didn’t have an answer for that. But his challenges had finally hit home. When I thought about it, I couldn’t do the “Rastafari” call and response because I didn’t believe Selassie was God.

You can’t be a Christian without believing in Christ, and you can’t be a Rastafarian if you don’t believe in the holiness of Ras Tafari (Selassie’s name was Tafari Makonnen, and Ras means “King”). When Selassie visited Jamaica in 1966 and learned about the Rastafarians, he told them he wasn’t God, but the Rastas couldn’t be dissuaded.

You can’t be a Christian without believing in Christ, and you can’t be a Rastafarian if you don’t believe in the holiness of Ras Tafari (Selassie’s name was Tafari Makonnen, and Ras means “King”). When Selassie visited Jamaica in 1966 and learned about the Rastafarians, he told them he wasn’t God, but the Rastas couldn’t be dissuaded.

Even his death nine years later, in the summer of 1975, didn’t dampen their enthusiasm. In fact, a number of reggae songs were released within days disputing Selassie’s death or, in typically twisty Rasta logic, saying it didn’t even matter if the man was dead because the God persisted. Bob Marley’s song Jah Live argues that point in a roundabout way.

Fools say in their heart

“Rasta, your God is dead.”

The truth is an offense but not a sin

Is he who laughs last, children, is he who wins

It’s a foolish dog, bark at a flying bird

Sheep must learn, children, to respect the shepherd

Let Jah arise

Now that the enemies are scattered

But for me, the revelation that I wasn’t a Rasta after all wasn’t sad. I didn’t feel like I’d wasted those years of my life. On the contrary, I believe that time helped lay the foundation for who I became–who I am today. And it all started on the floor of that apartment, a new world unfolding in my ears.

Rastafari!

![]()

As much as I loved the music and was drawn in by the messages, the thing about Natty Dread that really made me feel it was the expression of alienation in many of the lyrics. But also—and maybe I’m imagining things—I felt alienation and loneliness in the sound and ambiance of the record. Alienation that’s taken musical form. A plea. A frantic dispatch from behind enemy lines.

I grew up transgender in a world that didn’t yet have words or concepts for who I was. The words and concepts didn’t exist. But I existed, and I existed utterly alone. I had friends, but how could I ever tell them who I was when they had no framework to understand me? I didn’t even understand me. I was alone with the most fundamental part of me. The part no one could see. I was as alienated as a human can be.

So, I guess it makes sense that I connected with the alienation in Bob’s music and much of the reggae I heard. But I think maybe because I felt that connection so deeply, I also felt the redemptive parts of the music and the message more than I might have otherwise. The hopefulness. The resistance. They filled me with joy when joy was in short supply.

They still fill me with joy.

But I’m no longer alone.

Discover more from Wow. A blog.

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.